I. Ignored, but essential

Its reputation is foul and dirty, but some people who know it well believe the river that snakes through East Texas is a natural treasure and vital to life

The Sabine River slinks ignored and unloved through the swamps and bottomlands of eastern Texas, below rolling pine hills, beneath uninviting walls of slick, red clay.

Alligators lurk in its backwater sloughs. Snakes – lots of snakes – writhe across its waters. They sun in the branches of hardwood trees, and, so the old-timers warn, they sometimes fall from low, hanging limbs, onto the laps of unsuspecting fishermen.

People die there, and bodies are dumped there. Every two or three years, one sheriff told me, his deputies pull a soggy corpse from some out-of-the-way crossing. Texans are taught to revere the Rio Grande, and they vacation beside the cool, clear waters of the Guadalupe. But around the Sabine, it seems, they tend to keep their distance.

“There are people that go over it every day and don’t even look at it,” laments Tom Gallenbach, a local game warden.

From a highway bridge, the Sabine doesn’t look like much – tangles of brush and a few downed trees. Beer cans and muddy banks. A brown ribbon of water that disappears around a bend. But my buddy Jake and I got to talking, and we figured there had to be something more to the river than mud and mosquitoes.

After months of scheming, we were ready to see for ourselves. We figured we’d camp on sandbars and fish for our dinner, just roughing it, and we’d go as far as we could in four days. We decided to ignore a weather report that called for rain, and we brought camping gear, food, fishing poles, bug spray and a flat-bottom boat on loan from Shipp’s Marine in Gladewater. We also had a shotgun, just in case.

And so, on a gray, cloudy Tuesday in June, we set out to look around the bend.

How bad could it be?

The Sabine River begins in northeast Texas, just south of Greenville, where three forks merge in the Lake Tawakoni reservoir.

Several times a year, floods on the Sabine wash the banks out from under trees. The trees cave into the water, where they snarl debris in a current that can run from lethargic to raging in a matter of minutes. Where the river is narrow, the logjams make navigation tricky and often impossible.

Ignorant but not stupid, we sought advice for our trip from experts like Shaun Crook, a state wildlife biologist whose research carries him up and down the river throughout the year.

“It can get dangerous,” Crook told us. “If the river’s high and you don’t know what you’re doing, you can get in a pickle real quick. I’ve almost flipped several boats when you get out in that fast current.”

Crook is a tall man with a grizzly beard. He wears a denim shirt, tucked into denim jeans, tucked into knee-high rubber boots.

It gets muddy where he works.

As the staff biologist for the Old Sabine Bottom Wildlife Management Area, a 5,700-acre reserve northeast of his hometown of Lindale, Crook has explored the length of the river along the Old Sabine, and he didn’t think we stood much of a chance boating through it. Spring floods had receded, and the water was full of downed trees.

“You’re probably gonna come into contact with logjams you can’t get around when it’s that low,” he said. “Sometimes you can go through them if they’re real loose, but it’s gonna be tough getting up and down that river right now. You probably won’t be able to run the whole length of the WMA.”

But Crook had a plan. He had been spending much of his time doing paperwork, or counting birds and analyzing trees in the forest. He was itching to get back on the river. He didn’t think we could handle it by ourselves, but he didn’t mind taking us for a ride in his boat, courtesy of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

We put into the river at a public boat ramp of mud and dirt at the end of a rutted truck trail that cut through the wildlife area. The motor hummed as Crook sped around the many logjams that cluttered our path. Occasionally, low tree branches smacked us in the face.

“Watch out,” Crook shouted. “Sometimes you’re just gonna have to duck down and take it.”

We cruised toward our destination south of the East Texas town of Hawkins, a journey that could take thirty minutes or four hours, depending on water levels that had been falling about a foot a day.

That day, the river at the Old Sabine was about six feet deep. By late summer, Crook said, the river is so shallow he can wade across it without getting his socks wet inside his rubber boots. But that can change in a hurry, he added. When the winter and spring floods arrive, the water can surge over thirty feet high.

When the river rises especially high, usually in the winter or spring, it spills over the banks. The floodwaters fill low areas and create wetlands, and those wetlands trigger an important cycle in the health of the river, Crook explained.

“The wetlands act like kidneys to filter out pollution, heavy metals and effluence” – think sewage – “that come from up above us,” he said.

In other words, they operate like the tap-water purifiers you’ve seen in kitchen sinks.

Harmful things like sewage and silt are churned up in the current of rivers. But when the floodwaters spill into the bottomlands, the dirty stuff is swept along with it.

Tree roots and other vegetation in the wetlands trap and break down the harmful bits. Meanwhile, the floodwater caught in the wetlands soaks into the ground. Eventually, it seeps back into streams, lakes and rivers – and eventually our drinking water – while the harmful sediment is left behind. The silt that makes water cloudy is also filtered out.

That’s how it has worked for thousands of years, but it’s happening a lot less, Crook said. Texas has lost three-quarters of its bottomland hardwood trees in the past two centuries. And for the past four decades, water flow and floods along the upper Sabine have depended on water levels in Lake Tawakoni, a reservoir built at the head of the river.

“Before Tawakoni, we had larger and longer floods,” Crook said.

Until heavy rains in 2007, he said, the Old Sabine Bottom hadn’t flooded in about five years. After the drought, many ducks and other wetland creatures are only starting to return.

“There’s always a threat to bottomland hardwood habitat, but the biggest threat right now is reservoirs, because everybody needs water,” he said.

So how does one strike a balance between conservation and our growing thirst for water?

Crook laughed and shook his head.

“I don’t know,” he said. “It’s a very, very sticky situation.”

Scaring turtles, skirting logjams

Crook nosed the boat through a jumble of twigs and sticks. He eased off the gas.

A fallen log straddled the water like a small bridge, just a few feet above the surface. We crawled into the bottom of the boat and coasted underneath it, clearing the log by inches.

“All right, we’re good,” Crook said. “Till the next logjam.”

As we regained speed, snowy egrets and little blue herons glided alongside our boat before veering over the trees. Turtles plopped into the water, and palmetto plants waved like spiky green fans on the tall banks. It was hard to fathom that less than 25 years earlier, this place had almost been submerged in the bottom of a reservoir known as Waters Bluff.

It would have been an excellent reservoir, according to Jack Tatum, a Sabine River expert who spoke with me before our trip began. Tatum is the water resources manager for the Sabine River Authority, the state agency that oversees the river and its watershed area.

The would-be reservoir would have supplied the water needs of the region for years to come, he said, and it would have taken much of the guesswork out of the supply process.

“In Texas, our rivers are ephemeral in nature. There is a lot of flow at times and no flow at other times. Unless you have a storage project, how do you plan for future water needs?” he said. “Even with conservation, if you’re gonna double the population of the state, you’re gonna have to meet those needs.”

Conservation groups fought the construction of Waters Bluff. In 1986, an 84-year-old hunting club on the north bank of the Sabine – the Little Sandy Hunting and Fishing Club – turned over its 3,800 acres to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. The river authority sued, but a judge’s order effectively killed the plans for the reservoir.

The boat goes airborne

Two decades later, Little Sandy club members still hunt and fish with exclusive rights to the federal refuge. Several people have built covered barges that float on the river and provide shelter to campers and fishermen.

Researchers are studying the many alligators that grow long and skinny in the Little Sandy’s oxbow lakes, and more importantly, the refuge is home to what many people consider the last substantial forest of old growth bottomland hardwoods in Texas.

“There are some trees over there that us three holding out hand to hand couldn’t reach around them,” Crook said.

Across the river from Little Sandy, at the Old Sabine Bottom, state wildlife managers are allowing younger trees to grow. The forest will reach old growth status in about half a century, Crook said.

The biologist rounded a bend in the river. He came to another obstacle – a downed log that peeked two or three inches from the water’s surface.

“OK, hang on,” Crook said. “I’m gonna jump it.”

He mashed the accelerator and hit the log dead-on, seesawing his boat across. He jerked the propeller out of the water an instant before it would have crushed against the log, and we fell with a thud back into the river.

Soon we reached our destination – a farm-to-market bridge north of Tyler.

We had completed our first day on the river, and we were proud of ourselves. Tomorrow, though, would be different. We’d put into the river just outside Gladewater, a little oil-and-gas town between Longview and Tyler, and we’d be steering our own boat without Crook to guide us. Tatum, an avid kayaker, told us to expect more logjams and little concrete dams, called weirs, that might snag our boat as we floated toward Longview.

“Once you leave that bridge and you’re heading downstream, you’ve got to be prepared,” he said. “It’s a slow-moving river, but it’s misleading. You have to be careful because you can get into all kinds of things out there.”

Crook offered this advice:

“If you hear ‘Dueling Banjos,’ ” he said, “run like heck.”

* * * *

II. Born and raised

What’s to be found on the river? Fish, snakes, abandoned structures and oil rigs and sometimes people. And often, you’ll find a good story.

Towering concrete ruins have crumbled along the river. The encroaching forest wraps its vines around them, swallowing the ancient and abandoned structures.

Our little flat-bottom boat motored past massive pillars that rose from either bank of the Sabine River like monuments to a vanished people. We skirted wooden platforms that rotted on the river’s edge, as rusting pipes swayed in the current.

The water was wide, calm and greenish-brown as we boated downstream from Gladewater. Concrete blocks squatted like little pyramids on the banks, while others laid over like broken tombstones.

A snake slithered in the water. I remembered a word of advice from Ricky Maxey, a state wildlife biologist who has studied the river.

“I wouldn’t be overly concerned,” Maxey had said. “They’re just trying to make a living, looking for things to eat, and most of the time they’re looking to get away from humans.”

At lunch time, we tied our boat to a wide tree limb that shaded the water. Tall oaks and elms crowded the other bank.

“It’s so beautiful down here,” Jake said. “It’s so much prettier than I think about it.”

East Texas is also hillier than many people realize. Pressing on, we passed bluffs that towered thirty to forty feet above the river. On one, cows rested under pine trees, watching us as they chewed.

Approaching State Highway 42, a few miles south of White Oak, houses began to appear on the southwestern bank. A black dog swam in the water. Maybe his owner was nearby.

The Indians left their fish traps

Sure enough, the dog belonged to Don McClendon, a man who wore a handlebar mustache, Red Wing boots and a pair of short pants. He was spending his afternoon on an old John Deere tractor, leveling dirt at his future home site overlooking the river.

McClendon said he grew up nearby, exploring ancient Indian hunting and fishing grounds.

“I’ve found a zillion arrowheads down here,” he said. “Down about twenty feet from where your boat’s parked, there’s an old Indian fish trap.”

Up and down the river, he said, you can see Indian fish traps late in summer when the water’s low. Indians built U-shaped walls of river stone that looked like jetties, he said. The walls blocked the fish’s passage through the channel, leaving them easy prey for an fisherman’s spear.

The fish traps probably belonged to the Caddo Indians, who had been living in the Sabine River basin for around 800 years when the Spanish reached the area in the 16th century. Long before the Caddos, the basin was home to the 12,000-year-old Clovis culture, whose chiseled spear points McClendon and others still find on banks and riverbeds.

McClendon looked across the river, admiring the view. He said it’s a peaceful place to sit and drink coffee in the morning.

“You’ll talk to people who just think the Sabine River is an old, nasty, muddy river, but we swam in it all our lives, skied in it,” he said. “It’s just like a lake, but it changes every year. When it floods and goes back down there’s always something different.”

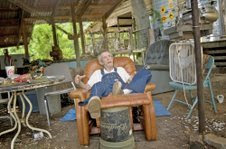

McClendon said we should introduce ourselves to his down-river neighbor, Elton Wayne Woodall. We found Mr. Woodall sitting on a high bank at the sprawling shack he’s been building since he moved in ten years ago.

“I’ve lived on the river a pretty good while,” the old man told us. “I was born and raised here, and I’ve been as far as you can go both ways.”

Clean water and fine-tasting fish

Woodall was a trapper. Before he got sick a few months before we met him, he snared beavers, raccoons, bobcats and river otters along the Sabine.

Woodall was a trapper. Before he got sick a few months before we met him, he snared beavers, raccoons, bobcats and river otters along the Sabine.

After he caught a critter, he skinned and stretched it. He did his work in a shop he constructed on an island in a wide pond that sits in his front yard. A bridge carried him from his yard to his island, where he had privacy to work.

Woodall sold the pelts to a distributor in Canada. He also caught and sold catfish to the public. “Just show up and ask for them,” he said. “I’ve got them in the freezer. Don’t know how many I have left, since I’ve been sick two or three months.”

Woodall figured the nature of his illness was nobody’s business but his own. It was serious, though, and a couple of months later, his obituary appeared in the local newspapers. On the day we met him, the last Wednesday in June, he rested in a leather recliner under the tin-roof carport next to his house. An industrial-sized box fan blew cool air on his face.

When he was a child, Woodall said, his father ran trotlines on the Sabine, and he and his friends floated down the river on inner tubes. The river has changed dramatically since those days, especially in regard to the oilfield equipment that has been left to decay along the river banks.

“When I was growing up, you couldn’t even eat the fish in this river it was so polluted,” he said. “(Oilfield companies) just dumped that saltwater piss into the river, and the fish tasted bad. We had to fish above Gladewater to get fish we could eat. But it’s been cleaned up, and there’s good fishing now. The fish taste fine.”

Jack Tatum, the Sabine River Authority manager, had also told us about efforts to clean up the river. Some East Texans might think their river is dirty, but that’s just not the case anymore, he said.

In the 1970s and ’80s, the state government began cleaning the Sabine and other rivers of wastewater contaminants. Regulators streamlined the standards for water that pours into the river from industries and sewage treatment facilities, and the river authority and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality continue to monitor the Sabine and its tributaries.

Especially downstream from the industrial town of Longview, the Sabine’s watershed sometimes has low levels of dissolved oxygen, which can harm fish. A couple of monitoring sites occasionally show high levels of bacteria after heavy rainfalls, but the river water is generally safe, according to river authority reports.

Tatum said there are no restrictions on fish consumption or bodily contact with the Sabine River water.

“The river’s in better shape than it’s been in many, many years as far as water quality,” Tatum said. “We’ve come a long way in protecting our water. Generally speaking, the water quality is excellent throughout the Sabine watershed.”

Frog legs are good eating

Woodall said the Sabine River is home to more game now than at any other time in his sixty years. The previous weekend, he said, his grandchildren snagged around three dozen frogs.

“They go up and down the river catching bullfrogs with their hands. They’re really good eating,” he said. “We fry most of them, just like fried chicken.”

The afternoon was getting late. It was time to move on, but not before a caution from Woodall: “Y’all be careful. You can turn a boat over in that river,” he said. “I’ve done it a hundred times.”

Just as Tatum had warned, Woodall said to watch for the weir hidden just beneath the water between the next two highway crossings, Texas 42 and Texas 31.

“It’s bad dangerous,” he said. “I sunk my boat there in January and nearly drowned. Make sure you get out and have a look around before you do anything.”

First test of nautical skill

Old oil derricks stretched up from platforms on the water around Highway 42. The river seemed to narrow, and we dodged frequent trees that clogged the channel.

A few miles downstream from the highway, we had to stop.

A pair of trees had fallen from opposite bluffs. They formed a wall where they met in the middle of the river, snagging logs and limbs in a massive tangle of woody debris. A thick, gray snake slithered among the branches.

There was no way around.

The smaller of the two trees lay mostly submerged, peeking two or three inches above the water’s surface. Only the day before, our river guide had jumped a similar log in his flat-bottom boat.

“Oh, we got this,” I said.

Jake, the level-headed one, was not so sure. The logjam diverted the swift current under and around itself, and he feared that if the boat struck high center, we would be sucked into the water’s path and spun sideways, quickly capsizing.

To make matters worse, a sharp knob jutted from the smaller tree in the only place we thought we could cross. What if we gashed the bottom of our borrowed boat?

We docked to have a look around.

Clinging to exposed pine tree roots, we scrambled up a steep bank of red clay. If we unloaded our gear and somehow hoisted the 16-foot-long boat over the bank, we thought we could walk it about a hundred yards along a game trail and put in just downstream of the logjam. It was an hours-long prospect.

On cue, storm clouds rolled in, dark and ominous.

We had to go for it. We gunned the boat toward the lower log to hit it full-speed and jump it, hoping we wouldn’t crush the propeller. We were about to hit the log. But at the last second, we veered away. We raced for it a second time: We got closer. We were almost upon it. We turned off.

“I just can’t do it,” Jake said. “I’ve never gone over anything like that.”

Defeated, we called my brother Dan and asked him to pick us up. As we backtracked to the highway crossing, the first of the raindrops stung our faces and rippled on the river.

Call us dismal failures

Back at the highway bridge, a man named Ronnie King Jr. was loading a boat the size of a tank at a private ramp just off the roadway. King, from nearby White Oak, had spent the afternoon riding the river. He said our logjam was pretty easy to cross when heading downstream.

It was only a little trickier on the way back up, he added. That didn’t make us feel any better.

“When you’re about to jump a log, run it like it’s stolen,” he advised. That meant driving as fast — and recklessly — as possible.

King gave us his phone number and the numbers of a few of his buddies.

“We run the river pretty hard,” he said. “If, God forbid, you lock a motor up, you give us a call and we’ll get you drug out of there.”

It was only our second day on the river – our first by ourselves – and already the trip was in peril. What if we had gotten over that logjam only to face another, meaner one just a few miles downstream?

Dan showed up. He rolled down his window and shook his head at me.

“I hope this isn’t a sign of what’s to come,” he said.

* * * *

III. Lost Towns

Along the river sit ghost communities – once thriving towns in the 1800s that fed on the Sabine and became extinct as the Civil War raged

Lightning flashed in the western sky. A thunderstorm rolled toward the river. And here were two guys climbing into a metal boat on an open body of water. Smart.

A rainy night approached on the second day of our journey down the Sabine River. We sat underneath a bridge in Lakeport, feeling like a couple of bums, as we waited for the downpour to subside.

This trip was not going according to plan.

A few hours earlier, Jake and I had come to a logjam we couldn’t get over or around. After backtracking, we hauled our borrowed boat to the next public boat ramp, in Lakeport. The maneuver bypassed most of the Sabine around Longview and Gregg County, a narrow, winding stretch that several people said was worth seeing.

“When you get to that part of the river, it seems like you’re lost in the middle of nowhere,” Ronnie King Jr. had told us. “It’s quiet, and you don’t see civilization. It’s just you and your boat and your rod and your reel, enjoying life.”

We missed the chance to look for any signs of Fredonia, a river port that once bustled on the southern banks of the Sabine River, long before anyone ever heard of a younger town a few miles to the north – Longview.

Fredonia, a town that vanished

In the years between Texas Independence and the Civil War, little towns sprang up at ferry crossings all along the Sabine in East Texas. The cotton trade was thriving, and plantation owners loaded their crops onto barges that steamed down the river to New Orleans and Galveston.

Haden Edwards, a pioneer and entrepreneur who lived in Nacogdoches, had been run out of Texas in 1827 for leading a failed revolt against the Mexican government. He returned during the Texas Revolution, and in 1839, he founded the town of Fredonia where Interstate 20 and Farm-to-Market Road 2087 meet south of Longview.

By the 1850s, the ferry crossing and riverport had three warehouses and forty to fifty buildings, including a brick kiln and a post office.

During the Civil War, men left the town to fight, and the ones who stayed couldn’t find a market for their cotton. The town disappeared. In the years that followed, freed black people established a settlement a couple of miles to the south. They also called their community Fredonia, and it’s still there today.

But we missed all that. The rain and fast-approaching nightfall kept us from heading upstream on a search for a town that’s no longer there.

So instead, we sat under the bridge in Lakeport, drinking cans of cold beer and trying to stay dry.

Careening over alligator gar

When the storm passed, after an hour and a half, we were feeling much better about our situation. We left the shelter of the bridge, and the river was dark and green in the shadows.

We were left with just enough twilight for me to pop the top on another beverage and for Jake to set up our camp on a muddy spot a mile or so downriver, beside a tree with gnarled limbs that stretched down to the water. We split a can of beef stew, and slept like rocks.

In the morning, the previous night’s rain dripped from saturated bluffs and fell in droplets to the river. Red clay bled down the banks. Jake let me steer the boat, and I promptly ran over two alligator gar and drove sideways onto the bank. A corner of the boat dipped below the surface, filling our vessel with water that Jake scooped out with a plastic water bottle. He resumed control of the motor.

For generations, Jake’s family has lived on land that abuts the river, and we stopped to pick up a couple of gas cans he had hidden at the clearing where he and his relatives have picnics and fish fries, and where they spend lazy afternoons casting lines into the brown water.

Along the way, we looked for signs of the ferry that once transported people to and from the rowdy river port of Camden, where you could drink in saloons and spend the night in a two-story hotel in the 1850s, as long as you didn’t mind sharing your bed with a stranger.

Where’s this thriving river port?

Camden grew in the 1800s at the river crossing of the Trammel Trace, a path that was first used by Indians and later became one of the main routes for Americans who were settling in Texas. A stagecoach line connected the town to Shreveport and Henderson.

Jerry Don Watt, an amateur historian from the nearby town of Tatum, calls Camden the former “hub of East Texas” and the “queen city of the upper Sabine.” Like Fredonia, Camden declined during the Civil War. When the Southern Pacific Railroad chose to bypass the town in 1871, the remaining white residents moved to Tatum and the newly formed town of Longview.

Many of the black residents stayed. In 1949, they changed the name to Easton, and about 550 people still live there.

“It’s hard to imagine today that Camden was such a thriving community,” Watt said. “It is my belief that if the railroad had followed the old stagecoach line, then Camden would have been what Longview is now, the largest town in this part of East Texas.”

Back on the river, we heard churning water in the distance. Upstream from Texas Highway 43, a couple of hours past Easton, we came to the first of the lignite shoals: seams of craggy black coal that snag boats in the water.

They are the same deposits that miners dig from sites around the region, and we had been warned about the many shoals that appear throughout northern Panola County. When the water’s not high, they create rapids and even a two-foot waterfall on the wide, shallow river.

“There’s a pretty strong hydraulic current behind that thing,” Maxey, the state wildlife biologist, had advised. “Be safe and look for where the most water passes.”

The current pulled us toward the churning water as we searched for the safest place to enter. The propeller scraped the lignite, and Jake killed the motor and lifted the prop from the water.

We would have to paddle. The boat plunged into the rapids, and we slipped into a whirlpool, spinning backward. The boat stuck against the sharp lignite, screeching like fingernails on a chalkboard. Jake leaped into the knee-high current to right the boat; I used our one paddle to push off against the rocks.

We jerked free abruptly, throwing me down into the boat. Jake hopped in, and we again were on our way in water that rushed from the rapids. Our next stop would be at U.S. Highway 59, a road that runs from Mexico to Canada and crosses the river just south of Marshall.

Gone fishin’

Spoiled chicken livers might not do much for you or me, but they drive the catfish wild, according to the men and women who were casting lines into a more calm flow at the Highway 59 bridge, less than an hour’s ride from the rapids.

Sandra Hodge lined nine fishing rods along the wide, flat bank. She and her sister, Sissy Bishop, were hoping to lure a catfish on their Thursday afternoon away from work.

“If you’ve got a lot of stress, come down here and watch that water, and it just washes away your concerns,” Hodge said. “But I do wish we’d catch something.”

Hodge lives down the road in Carthage. She said she enjoys cool evenings at this spot, listening to the water lap against the banks. She fishes whenever she can, and she’s the owner of nineteen fishing rods. Each has a name scribbled on it in permanent marker. As we visited, “Bumble Bee” and the others stood with no pulls from the water.

“I’m not warped,” she said. “I just like to name my rod and reel.”

Hodge said her husband taught her to appreciate the river and its bounty. He built and sold minnow traps for spending money when he was a child. What’s more, the community of Hodge Slough in north central Panola County is named for her father-in-law, who ran trotlines there.

“My husband will not eat a catfish out of a lake,” she said. “He says you can taste the mud. River water is running and clean. The fish are a lighter color blue, and they just look cleaner to me. I love the Sabine River.”

She loves the river, she said, but she remains careful around it.

“The water may look calm and safe, but the current and undertow are what get you,” she said.

Unwelcome guests

We pressed on. Beaches of startlingly white sand mounded up on the river bends through Panola County. Along this isolated stretch, cypress swamps lined the mouths of the many streams and sloughs that merged with the river. We saw a doe, more turtles than we could hope to count, and a pack of wild hogs that snorted and ducked into the brush as we came near.

The sun was falling behind willow trees that swayed in the breeze.

We found a sloping sandbar tucked behind a sharp bend, and we pitched the tent. We peeled off our rubber boots, dug our toes into the sand, and set out to put our nameless fishing rods to work. Unfortunately, we’d picked the wrong kind of bait. When we cast the line, the hook sailed in one direction and the bait flew to the other. There would be no fried catfish with our dinner of yellow squash and mashed potatoes.

We sat in camping chairs on our beach in the middle of nowhere, and we had the place to ourselves.

Or so we thought.

A rumbling came from the river’s bend. At the edge of the forest, a woman watched us from her four-wheeler. Without word or sign, she backed into the woods and was gone.

Ten minutes later, we heard a boat motor approaching from upstream. A man and a boy nosed around the corner. Like the woman, they took a quick look and reversed out of sight.

Then all three boated by. The man had short, red hair and overalls. He kept his eyes locked on the opposite bank.

This was clearly their sandbar.

But we had a right to it as well, according to Tom Gallenbach, the game warden who patrols the Sabine.

“As long as you’re below the permanent vegetation line, you can camp there,” he had told us. “Some people will try to run you off, but most people know you can camp there.”

Did these people know that?

* * * *

IV. River Fellowship

They share freshly caught catfish with each other, then fry it under tall shade trees. The kids swim till the sun sets – and beyond. On the river, there’s a hidden community that most people don’t even know exists.

We were being watched as the sun set over the river.

It was the end of our third day boating down the Sabine, and we knew we had pitched our tent on someone else’s sandbar. But it was getting too dark to search for another campsite. Anyway, state law says people can camp along rivers, as long as they don’t venture beyond the banks.

“If there’s trees, you’re trespassing,” Gallenbach had said.

There were no trees on this sandbar. Jake and I weren’t budging. We waved hello to the people as they passed in their boat. Maybe they were just checking their trotlines. Maybe.

After dark, two hoot owls called to each other, “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you all?” The shadowy thicket surrounded our camp on three sides. Something rustled in the brush.

“Did you hear that?” I said.

The noises seemed to be getting louder.

“It sounds like people talking in the woods,” Jake said.

He fetched his shotgun from the tent and laid it across his lap. Moonlight rippled on the water. We sat in our chairs on the sandy beach, and we waited. Twigs and branches crackled in the forest. There was a loud crash, and thrashing. Whatever it was, it was nearby, and it was getting closer.

Then came the squeals and grunts.

“Oh, hogs,” Jake said.

They rooted around for a while before returning to the forest.

We left early the next morning. We didn’t see the people again.

Slippery otter slides

East Texans who have only seen the Sabine from bridges around Longview might be surprised by a glimpse of the river as it winds toward the Louisiana border. Above Longview, the Sabine is muddy and narrow, with banks of slick, red clay. Young oaks, elms and other hardwoods crowd the water below tall bluffs where skinny pine trees stand.

As the river travels southeast, the brown water takes on a greenish hue. Drooping willows line wide, gentle banks and sandbars.

On a few of the steeper banks we thought we saw “otter slides,” places where playful river otters slip on their bellies, face-first, into the water. Once killed for being predators, the sleek, web-footed mammals are on the return, Maxey had said.

“They’re very curious animals,” he said. “On my encounter with them, I was deer hunting, leaning against a tree being very quiet, when one popped its head up and looked at me. Then five more popped up their heads, and they took off.”

Only a few miles downstream from our campsite, a tall bluff of layered gray rock rose from the bank, wrapping around a long river bend. It stretched on for several minutes before descending into the water.

Later, Slim Barber, an 81-year-old man from De Berry, told us we had seen a seam of lignite coal that is famous among people who run the river. It’s the Pulaski bluff, he said, the site of an old town that served as the seat for Harrison County in 1841 and Panola County in 1846. Today, all that remains is a historic marker.

By midmorning, we were getting hungry. We cruised under FM Road 2517, the last highway crossing before Toledo Bend, where several men fished from boats in shady spots along the banks.

We planned our next stop to coincide with lunch time, and it paid off: river guide Jane Gallenbach greeted us with slices of homemade pizza, topped with spicy sausage ground from wild hogs – hogs that had been shot on her property.

“We don’t buy a lot of meat,” she said. “Every once in a while you need real beef, but most of what we eat is wild.”

A Sabine queen

Gallenbach, the “queen of the Sabine,” grew up hustling bait for her fisherman father. She said the river has gotten wider and shallower in the years since then, after construction of Toledo Bend in the late 1960s.

“It wasn’t anything to just wade across the river,” in the summertime when she was a child, she said. Now her section of the Sabine can stretch a mile wide during the flood season.

“The river’s getting wider, but it’s getting shallower,” she said. “It’s changing every time the river comes up, and I think a lot of that has to do with trees that are being cut up closer to the banks. It’s just washing away.”

Gallenbach said logging companies own much of the land along the Sabine River in her county, and some of them clear-cut their timber to the riverbank.

When those trees are gone, she said, the force of the rising current eats away the banks, and the sediment fills in the riverbed. When the water drops after a big storm, sometimes sandbars have shifted from one side of the river to the other.

Too high, or too low?

On the Sabine River, expect to get muddy, and expect to get wet.

“That’s just the way it is,” said Gallenbach’s husband, Tom, the game warden. He said the river can rise or fall six feet in a day.

“A lot of people say when it’s too high, it’s too dangerous, when it’s low it’s too dangerous,” he said. “It’s never just right.”

The changing conditions keep the river guide on her toes, especially when she’s leading people to her prime fishing spots. The Gallenbachs own the River Ridge campground and guide service south of Carthage.

Every spring, thousands of people from across the nation descend on the spot upriver from Toledo Bend to fish for white bass. The fish, which were introduced to the reservoir a few decades back, swim upstream to spawn in river tributaries.

“I can remember in my late teens my dad just having a fit because the white bass were getting on his trotlines,” she said. “We do much more white bass than we do catfishing now.”

Catfish is still king

We thanked the river queen for her pizza and were back on the open water. Down river from the Gallenbachs’ place, we bumped into Bill Dennis, a self-described river rat who was running his trotlines on a Friday afternoon.

“I’m catching fish,” he said. “That’s why everybody keeps coming down here, because they want some fish.”

Dennis steered the boat while his friend, Jeffrey Anderson, fished the hooks from the water. Anderson, of Carthage, felt something tugging on the line, and he pulled from the water a catfish about as long as his arm. Dinner.

“We’re gonna have a fish fry,” Dennis said. “Y’all stick around; we’ll feed you.”

First wild hog sausage, and now catfish. Things were looking up. We motored the ten or twenty minutes to Dennis’ home at the Yellow Dog campground near Louisiana, and we pulled our boat onto the bank.

Life at Yellow Dog

For the past couple of months, Dennis said, he had been living in a travel trailer by the public boat ramp maintained by the Sabine River Authority. Jugs of water, camping gear and cooking supplies were conveniently strewn on and around the picnic table.

For the past couple of months, Dennis said, he had been living in a travel trailer by the public boat ramp maintained by the Sabine River Authority. Jugs of water, camping gear and cooking supplies were conveniently strewn on and around the picnic table.

“It’s like a community down here,” he said. “You’ve got a lot of good people, and a few that are not so good. Everybody keeps an eye on each other’s equipment. The majority of people respect my stuff.”

Dennis wore patched blue jeans and a T-shirt that might have been white at some earlier time. He’s from Laneville, a farming community in Rusk County, and he used to drive a truck for a living. Now that he’s retired, he said, he’s a river rat.

And what’s a river rat?

“A river rat just sits here and enjoys the river, loves the river,” he said. “You hang out, and a bunch of people infiltrate the place. They love to be around people who live down here.”

Anderson hung the catfish from a large hook and pulled away the skin, and Dennis filleted the fish and dropped the chunks into a bucket for later. He said he checks his trotlines throughout the day, but he rarely tastes what he catches.

“I eat fish maybe three or four times a year. I just love to fish. I give enough away to sink a battleship,” he said.

It was a Friday. He figured he’d be giving away plenty that night.

Some kind of heaven

As the lazy afternoon wore on, more and more people showed up. Children leaped from a tall bank into a cove in the river, and the women splashed mud on each other.

One woman, sultry and seductive, emerged from the river in a tube top and bottle-blond hair. Jake admired the spatters of mud and neon paint that adorned her toenails.

“Miss Cathy?” Jake asked. “Do you mind if I make a photograph of your feet?”

“How do you know my name?” she asked him.

It was an easy question. The name “Cathy” was tattooed across her lower back, just above her butt.

“I saw your tattoo,” he answered.

“You know why that’s back there, don’t you?” she said, rather suggestively. Jake seemed to be getting very uncomfortable.

“I think I have an idea,” he replied. He made a hasty photograph and escaped Cathy’s advances – for the moment.

Meanwhile, Anderson tended the fish fryer. His girlfriend, Ginger Williams, went off to find an old car hood. She chained it to the back of her four-wheeler and offered sled rides through the mud puddles.

“I grew up here,” Williams said. “I was actually born on the Sabine River, because Mama and Daddy had a flat on the (Farm-to-Market Road) 2517 bridge” on the way to the hospital.

Texas country music blared from Anderson’s pickup, and Jake was making his best photographs of the trip. But he was being watched. Cathy and her friend, a lady whose exposed midriff spilled over her bikini bottom, called Jake over to the campfire.

“You want some pictures?” Cathy asked.

“Um,” Jake stammered. “Maybe later.”

There would be no later. Vigilant, Jake spent the rest of the evening avoiding her clutches. By nightfall, nearly 30 children were swimming in the moonlight – four or five of them belonging to Cathy – as she and the other parents relaxed around Dennis’ camp. They picked at the fish, drank beers and passed around a bottle of whiskey. At one point, Dennis broke up a fight and sent the troublemaker home with a stern talking-to.

“Redneck heaven,” they called this place.

Saying goodbye

From Yellow Dog, the Sabine River flows into Toledo Bend. It fills the massive reservoir and heads south, marking the boundary between Texas and Louisiana. Some people, like the trapper Elton Woodall, have gone as far as a person can get, from the headwaters south of Greenville to Sabine Lake in Port Arthur.

But our journey was over. We said goodbye to the people at Yellow Dog, and we drove back to Longview.

We crossed the river at Interstate 20. From the bridge, we couldn’t see a thing.

23,737 responses to “Life on the Sabine”

Awesome website you have here but I was wanting to know if you knew of any discussion boards that cover the same topics talked about here? I’d really like to be a part of community where I can get responses from other experienced people that share the same interest. If you have any recommendations, please let me know. Thanks!

Pornstar

Porn site

Porn

Sex

Porn site

Buy Drugs

Scam

Good day I am so delighted I found your blog, I really found you by accident, while I was searching on Yahoo for something else, Anyways I am here now and would just like to say cheers for a fantastic post and a all round entertaining blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to browse it all at the minute but I have book-marked it and also added your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read more, Please do keep up the superb work.

Buy Drugs

Buy Drugs

Porn

Pornstar

Its such as you read my mind! You seem to grasp a lot about this, like you wrote the ebook in it or something. I believe that you just could do with a few percent to drive the message home a little bit, however other than that, that is magnificent blog. A great read. I will definitely be back.

Viagra

Buy Drugs

Viagra

Viagra

Viagra

Sex

Viagra

Buy Drugs

Pornstar

Viagra

Porn site

Porn site

Attractive section of content. I just stumbled upon your blog and in accession capital to assert that I get actually enjoyed account your blog posts. Any way I?ll be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently quickly.

Pornstar

Viagra

Wonderful post however I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this subject? I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a little bit further. Bless you!

Porn site

Sex

Porn site

Hmm it looks like your site ate my first comment (it was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I wrote and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I too am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new to everything. Do you have any helpful hints for novice blog writers? I’d certainly appreciate it.

Porn site

Viagra

Sex

Sex

Thanks for the a new challenge you have unveiled in your writing. One thing I want to reply to is that FSBO relationships are built as time passes. By bringing out yourself to owners the first weekend their FSBO is actually announced, prior to the masses commence calling on Thursday, you build a good network. By giving them resources, educational elements, free reviews, and forms, you become the ally. By using a personal fascination with them in addition to their predicament, you develop a solid link that, on most occasions, pays off in the event the owners decide to go with a real estate agent they know as well as trust — preferably you actually.

Amazing all kinds of amazing tips!

Sex

Buy Drugs

Buy Drugs

Porn

Buy Drugs

For the best in San Jose Airport Transportation Service, rely on our SJC Limo Car Transfer Service. Enjoy luxurious SJC Car Service, reliable SJC Limo Transfer Service, and efficient Airprot Transfer SJC for a seamless travel experience with SJC Limo.

Incredible! This blog looks just like my old one! It’s on a totally different topic but it has pretty much the same page layout and design. Outstanding choice of colors!

Porn site

Pornstar

I?ve been exploring for a bit for any high-quality articles or blog posts on this sort of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this site. Reading this information So i?m happy to convey that I have a very good uncanny feeling I discovered just what I needed. I most certainly will make certain to don?t forget this website and give it a glance on a constant basis.