Yolanda Sanchez Perez, a hardworking grandma, lives with 13 of her grandkids on a muddy piece of land outside of town.

The only bathtub on the property is in a worn-down travel trailer in the backyard. The trailer has no running water. When it’s time to bathe, the family hauls it in five-gallon buckets.

The older boys sleep there in the trailer. They’ve barricaded the door so that it won’t flap open in the wind. The older girls share twin beds or sleep on the floor in a portable office building, which has been converted into the main living space. That’s where the kitchen and toilet are. Perez, 49, sleeps with the little ones in a shed around back, as long as the weather cooperates.

“I can’t stay here now because it’s too cold,” she says. “We have had good times in our lives, but now is the worst time.”

Perez is standing in the little shed on a Thursday afternoon, a day when the temperature will fall to 23 degrees. She’s rubbing her shoulders to keep herself warm. Her hair is pulled back in a short ponytail, and she smiles like crumpled cardboard. Now walking out of the shed, she presents the water hose where she washes the children’s clothes. In another direction she points to a shower nozzle that pokes out of a large particleboard box. It’s the family’s open-air shower in the summertime.

She walks through the backyard, across the mud and scraps of carpet, to the boys’ travel trailer. She raps on the door. The oldest two, ages 18 and 19, are playing Nintendo Wii. They hit the pause button while Perez lifts some blankets to show what the teens sleep on. It’s a sheet of wood.

A local do-gooder installed the wooden platform so the boys wouldn’t have to sleep on the floor, but no one has provided a mattress.

“They say they’ll do things for me, but they didn’t do things for me,” Perez says.

That’s not true, though. Perez has long depended on the kindness of strangers. She can’t read, her car won’t start, and she has 13 mouths to feed. To hold her family together, she’s got to hustle.

Choosing bad roads

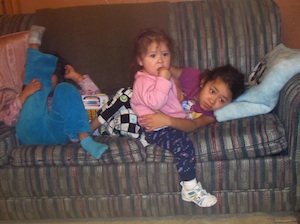

Perez is a boisterous and loud little woman, ever sighing over her lot in life. As the afternoon fades into evening, her voice grows hoarse from admonishing and scolding her brood. But she laughs a lot, too. She loves these kids.

Luis, the 4-year-old boy, wears a big, mischievous grin. He plays with a bouncing ball and a Batman car as he jogs circles around his grandma.

“Luis!” Perez says. “He’s running around here somewhere. The boy has no-good manners.

“Luis,” she says again, “come do your homework. This man, he is the police. He is calling the police on you.

“I always scare him to make him behave,” she explains, sighing to herself. “I’m gonna sit for another five seconds. Oh my God, it’s too much. But I would not give them up. I will not leave one behind.”

Her ex-husband helps when he can. He’s a house painter, carpet-layer and ceramic worker, and times are hard for him as well.

Perez has raised most of the children since they were babies, becoming their de facto mother as their parents scattered. Perez’s son is in prison, as is one of her daughters. Her other two daughters, according to Perez, are addicted to drugs. “When my girls grew up they chose the bad roads,” she says. “No one takes you there. You choose the bad roads.”

The parents receive food and financial benefits but don’t share them with Perez or the children, she adds. “I don’t know how the government gives them all this, and I don’t get nothing.”

On Thursday at the Perez home, in the sprawling Green Pastures neighborhood east of Interstate 35, two of the little girls have stayed home sick. The two oldest boys are in the trailer out back. The rest arrive on school buses from various campuses in the Hays Consolidated Independent School District. They come through the front door in waves, smiling politely and introducing themselves, then hitting up the kitchen for sandwiches, Hot Pockets or cups of ramen noodles.

Perez is worried about the food in the refrigerator. The fridge doesn’t feel cold enough, and she’ll need to move the groceries before they spoil to an older refrigerator out by the boys’ trailer.

“Get the ham, the baloney,” Perez tells Mayra, 17. “Tell the girls to get a bucket.”

“We’ll do it later,” Mayra says.

“OK. Are the girls doing their homework?”

Mayra is the family’s second in command. She has a child of her own, 18-month-old Isaac.

The other older kids all pitch in and tidy up after themselves, because Perez, a housekeeper by trade, insists on a neat and clean home. The living space is decorated with little elephant statuettes, a candle lighted to a painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe, and pictures of the kids taken with the rap star Chingo Bling.

Nearby is a framed, four-year-old page from the Austin American-Statesman. The main story on the page is about Perez and her many grandkids. At the time, the family was living in a mobile home without enough blankets or beds.

Perez was featured several times in the Statesman’s “Season for Caring” campaign in 2006. According to subsequent stories, the campaign spurred people to hold gift drives, raise funds and volunteer their time to assist the family. One business owner fixed the family’s heating and air-conditioning problems. Other individuals and businesses provided food, additional home repairs, clothes and more than $2,000 to Perez.

Two years ago — two years after the newspaper campaign — Perez lost her home.

“Times got harder for me, so I had to give it up,” she says. “My job got slow. The bank foreclosed on my house, and this is the only thing I can afford right now. When I have nowhere to go, this is where I end up with the kids.”

Since the move, Perez and her grandchildren have been the beneficiaries of an outpouring of coordinated giving. None of it seems to have been sufficient. The new washer and dryer? The washer doesn’t work. The new refrigerator? It won’t stay cold. The new stove? Only one burner gets hot. The new sofa, with the pull-out bed, is already broken.

“I’m stuck with a stupid couch, a stupid oven,” she says. “All I’ve got is junk.”

The backyard is crisscrossed with little ditches where a plumber, volunteering whole days of his time, has dug a series of new waterlines. He didn’t fill in the ditches when he was done.

“They made all this mess, and it didn’t help,” she says. “Those people didn’t do nothing. They just made a mess.”

Those people who made the mess, though, might beg to differ.

The Christmas gift drive

Every year around the holidays, the special education department at Hays CISD adopts one family for its “Angel Tree” drive. This past December, the department chose Perez and her children.

“What was really interesting and touching,” says Nancy Payton, the district’s student and family support coordinator, “was the list that they submitted. It only had maybe two things per kid. And they weren’t asking for ridiculous things. A baby doll, or a bike. Little things.

“Once we started talking with Yolanda we realized it was more than just a few gifts for some of the kids.”

Payton and her colleagues organized a basic-needs donation drive. They bought about eight gifts per child. They donated a couch, stove, microwave, kitchen chairs and several boxes of food, and they scheduled a work day on the Saturday before Christmas. About 25 volunteers spent the day cleaning and repairing the Perez property.

“It took probably four truckloads to get all of the stuff over there, and then on the workday we took six truckloads to the dump,” Payton says.

A plumber and electrician spent more than a day working on the property.

“The plumber actually donated a hot-water heater and ran the pipes so they could have hot water inside the house,” Payton says. Before, she adds, the family members had been heating their bath water with a propane tank. What’s more, the electrician hooked up a clothes dryer so Perez would no longer have to use a clothesline.

“They went way above the call of duty, really,” Payton says. “It was a very good day. We worked hard. We didn’t get everything done we wanted, but I think it turned out really wonderful.”

A few weeks later, Payton and her colleagues arranged to have the family’s dogs spayed and neutered, and that’s not all. “It’s still going on, this service project.”

But Payton isn’t sure what should be the next step to help the family.

“Do they need to be out there? No, that situation does not fit their needs,” she says. “They need a house that they all can be in.”

What Payton doesn’t know is that a new home has already been purchased for the family.

In the hands of angels

A few weeks after the “Angel Tree” workday, a school teacher named Tavia Hrabovsky went to see the Perez home for herself. She’d heard about the family from the counselor at her old school, Tom Green Elementary, where 4-year-old Luis attends prekindergarten.

What Hrabovsky found, she says, was a “ridiculous situation.” The family was in dire need, so she appealed for help from the Austin Angels, a year-old nonprofit group where Hrabovsky is the chief of marketing and development.

The Angels swooped in, raising $8,100 in little more than a week. One man purchased a 1,200-square-foot mobile home with three bedrooms and two bathrooms. The charity will be moving the home onto the Perez property when it is completely outfitted with bunk beds, linens and new appliances.

Soon, the entire family will be under one roof again.

On Thursday, Perez never even mentions the new home she’s getting. She’s got a more pressing concern — dinner.

Mayra is sitting at the kitchen table, filling out Valentine’s Day cards for the younger children.

“You don’t know any of your friends’ names?” Mayra asks Evannie, who is 7 and is wearing purple.

Evannie’s ponytail bobs as she throws her hands in the air. “Yes, but I forgot them!”

Perez is frying chicken wings on the one burner of the stove that works.

“Girls! Dino! Come eat,” she yells.

Teens and preteens emerge from the side rooms. Chris, 19, strolls, sleepy-eyed, from the room where he was napping.

“I know Chris smelled the chicken,” Perez says, teasing her eldest boy. “Chris loves to eat.”

Chris has a shaved head, likes to draw and is always laughing. When he was younger, he thought Perez was his mother, having been told that his real mom was his big sister. Chris’s cousin Dino, 15, is the soccer player. According to Perez, Dino’s mother promised him she would leave the drugs and be a better mother, but then she never came for him.

Chris’s brother Cesar, 16, wears camouflage pants tucked into military boots. His sweatshirt bears the initials of the Hays County Juvenile Justice Alternative Education Program, where students go when they’ve been expelled from Hays CISD. A 14th grandchild will be coming home from a mental institution in April.

Abagail, 13, is the smart one. Victor, 18, has a temper.

Another cousin, Stephanie, is a senior at Hays High School. She wants to get a job when she graduates, preferably in a clothing store, to save money to attend cosmetology school. “Mainly makeup and nails,” she says. “Hair’s not my main thing.”

When Perez serves the first round of dinner, everyone crowds around the table, sitting and standing, dousing the wings in hot sauce. When the food is gone the kids vanish.

“There’s more coming,” Perez hollers after them.

At first the kids don’t feel like taking a bath. It’s warm inside the office building. Outside, though, the night is blustery and cold, and a bath means a hike to the trailer around back. But then they change their minds. They fill the five-gallon bucket with warm water, and Victor lugs it through the front door, down the steps and into the dark.

62 responses to “For grandma raising 13, this is ‘the worst time’”

I do accept as true with all of the ideas you’ve introduced on your post. They’re really convincing and can definitely work. Nonetheless, the posts are very quick for starters. May just you please prolong them a bit from next time? Thanks for the post.

418516 623339Billiard is really a game which is mostly played by the high class people 146099

760485 980175I conceive this internet site contains some rattling superb info for everybody : D. 670241

711656 225822I?m often to blogging and i in actual fact respect your content material. The piece has really peaks my interest. I?m going to bookmark your content material and preserve checking for brand new info. 447003

259064 841285you?ve gotten an critical weblog proper here! would you wish to make some invite posts on my weblog? 2289

862357 426635Thank you for your quite excellent info and respond to you. 41152

856595 705178extremely very good post, i certainly really like this superb site, continue it 807021

993410 731164I view something genuinely unique in this web site . 402067

109444 617669Some truly exceptional articles on this internet web site , regards for contribution. 810551

610306 426072A person necessarily lend a hand to make severely posts I?d state. This is the very very first time I frequented your internet page and to this point? I surprised with the analysis you made to make this particular submit extraordinary. Magnificent process! 741250

932127 253637I gotta bookmark this internet website it seems really helpful invaluable 727279

817931 509534Flexibility means your space ought to get incremented with the improve in number of weblog users. 144991