For eighty-seven miles, the swift and shallow Blanco River winds through the Texas Hill Country. Its water is clear and green, darkened by frequent pools. But Spanish explorers named it the White River for the pale limestone they encountered along its banks and dramatic bluffs. Over the last two years, Wes Ferguson and Jacob Botter have paddled, walked, and waded the Blanco. They explored its history, people, wildlife, and the natural beauty that surprises so many who experience this river, and they recorded the human response to a deadly flood that has become yet another episode in the story of water in Texas.

This ‘captivating, necessary read’ is available now.

Click here to purchase signed copies directly from Wes. Or find The Blanco River in your local bookstore.

“Wes Ferguson tells the story of Texas’s secret river, the Blanco, examining its past while providing a vivid picture of the river and the people around it in the here-and-now that speaks to the larger issues of public access to Texas waterways and private property rights. After traveling around the state for more than a decade writing for Texas Monthly, I chose to reside and raise my family near the Blanco. It’s a good thing Ferguson did not write about my favorite swimming hole on the river; otherwise, I would have to shoot him.”—Joe Nick Patoski, writer, historian, and author of biographies of Willie Nelson, Selena, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and the Dallas Cowboys

“Wes Ferguson tells the story of Texas’s secret river, the Blanco, examining its past while providing a vivid picture of the river and the people around it in the here-and-now that speaks to the larger issues of public access to Texas waterways and private property rights. After traveling around the state for more than a decade writing for Texas Monthly, I chose to reside and raise my family near the Blanco. It’s a good thing Ferguson did not write about my favorite swimming hole on the river; otherwise, I would have to shoot him.”—Joe Nick Patoski, writer, historian, and author of biographies of Willie Nelson, Selena, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and the Dallas Cowboys

“Ferguson’s book is both a trustworthy guide into the rich and hidden history of the Blanco and a reminder of its sudden, destructive power. It also serves as a warning of the river’s extinction in the path of unchecked development. A captivating, necessary read for anyone who values this Texas treasure.”—Bryan Mealer, New York Times best-selling author of Muck City and The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind

“Ferguson’s book is both a trustworthy guide into the rich and hidden history of the Blanco and a reminder of its sudden, destructive power. It also serves as a warning of the river’s extinction in the path of unchecked development. A captivating, necessary read for anyone who values this Texas treasure.”—Bryan Mealer, New York Times best-selling author of Muck City and The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind

“The Blanco River is the spiritual bloodstream of my adult life, so I cracked this book open with some trepidation. I tried in vain to read chronologically, from one end of the river to the other, as Wes Ferguson so wisely arranges it. I couldn’t resist jumping to ‘my’ section of the river around Wimberley, where I fell in love, married on its banks, taught my kids to swim, and fought for the very water that flows between those heartbreakingly flood-ravaged banks. The journalistic style of The Blanco River allows Ferguson’s articulate narrators to provide fascinating historical and ecological details sure to enhance any stolen moments we spend floating down those clear, green waters. Even cranky old John Graves would surely be pleased to see Ferguson drifting gracefully from the silent wonder of the Guadalupe bass to the cacophony of Capitol politics, from floating daydreams to flooding nightmares, from the observations of Spanish explorers to the musings of those who inhabit the river’s increasingly modern towns. The Blanco River will stay in that short stack on my nightstand for months to come.” — Louie Bond, Editor, Texas Parks & Wildlife Magazine

“The Blanco River is the spiritual bloodstream of my adult life, so I cracked this book open with some trepidation. I tried in vain to read chronologically, from one end of the river to the other, as Wes Ferguson so wisely arranges it. I couldn’t resist jumping to ‘my’ section of the river around Wimberley, where I fell in love, married on its banks, taught my kids to swim, and fought for the very water that flows between those heartbreakingly flood-ravaged banks. The journalistic style of The Blanco River allows Ferguson’s articulate narrators to provide fascinating historical and ecological details sure to enhance any stolen moments we spend floating down those clear, green waters. Even cranky old John Graves would surely be pleased to see Ferguson drifting gracefully from the silent wonder of the Guadalupe bass to the cacophony of Capitol politics, from floating daydreams to flooding nightmares, from the observations of Spanish explorers to the musings of those who inhabit the river’s increasingly modern towns. The Blanco River will stay in that short stack on my nightstand for months to come.” — Louie Bond, Editor, Texas Parks & Wildlife Magazine

“I have been fortunate enough to swim the cooling Blanco in the heat of August, to walk its stony tributaries on a sharp fall day, and to skinny-dip at midnight in the healing waters of Jacob’s Well. And now Wes Ferguson and Jacob Croft Botter offer us in colorful words and perceptive photographs the opportunity to experience this same intricate magic and so much more as it flows from one of our state’s great rivers. Like a vital artery of the heart, the Blanco carries the life blood of water across the land and throughout the lives of many Texans. And with this volume, author and artist uniquely combine a sense of history, an eye for beauty and a narrative eloquence—all into a vibrant portrait of water and people and their eternally complex relationship. Welcome to a whole other chapter in the river photography and literature of Texas.”—Roy Flukinger, Senior Research Curator of Photography for the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin

“I have been fortunate enough to swim the cooling Blanco in the heat of August, to walk its stony tributaries on a sharp fall day, and to skinny-dip at midnight in the healing waters of Jacob’s Well. And now Wes Ferguson and Jacob Croft Botter offer us in colorful words and perceptive photographs the opportunity to experience this same intricate magic and so much more as it flows from one of our state’s great rivers. Like a vital artery of the heart, the Blanco carries the life blood of water across the land and throughout the lives of many Texans. And with this volume, author and artist uniquely combine a sense of history, an eye for beauty and a narrative eloquence—all into a vibrant portrait of water and people and their eternally complex relationship. Welcome to a whole other chapter in the river photography and literature of Texas.”—Roy Flukinger, Senior Research Curator of Photography for the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin

“Research and reporting can combine to create a kind of sublime poetry when in the hands of the right author. Wes Ferguson proves himself to be just such an author with his engaging The Blanco River. The Blanco is relatively short as rivers go, just eighty-seven miles. But its story is huge as it emerges from Ferguson’s book. He understands rivers; he understands this river. Complemented by Jacob Croft Botter’s photography, The Blanco River will affect how you think about this river in particular and rivers in general. It’s a captivating read.”—W.K. Stratton, author, Chasing the Rodeo, Boxing Shadows, Floyd Patterson, and Ranchero Ford/Dying in Red Dirt Country

“Research and reporting can combine to create a kind of sublime poetry when in the hands of the right author. Wes Ferguson proves himself to be just such an author with his engaging The Blanco River. The Blanco is relatively short as rivers go, just eighty-seven miles. But its story is huge as it emerges from Ferguson’s book. He understands rivers; he understands this river. Complemented by Jacob Croft Botter’s photography, The Blanco River will affect how you think about this river in particular and rivers in general. It’s a captivating read.”—W.K. Stratton, author, Chasing the Rodeo, Boxing Shadows, Floyd Patterson, and Ranchero Ford/Dying in Red Dirt Country

“In this sparkling, crisply written book, Wes Ferguson reveals how this quiet jewel of Hill Country rivers can evoke such jealous passions—and ultimately summon such destructive power.”—Steven L. Davis, President, Texas Institute of Letters, and author of Dallas 1963

“In this sparkling, crisply written book, Wes Ferguson reveals how this quiet jewel of Hill Country rivers can evoke such jealous passions—and ultimately summon such destructive power.”—Steven L. Davis, President, Texas Institute of Letters, and author of Dallas 1963

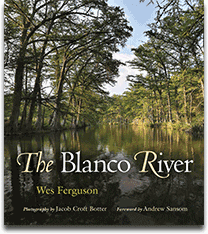

Chapter One: The White River

By Wes Ferguson

Photography by Jacob Croft Botter

Published by Texas A&M University Press (February 15, 2017)

Sponsored by The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment

Funded by the Burdine Johnson Foundation

ONE MORNING I went for a walk in the middle of the Blanco River. It was the dead of summer in Texas, and the Blanco had run dry, other than a few low pools trapped in depressions of the riverbed. From bank to bank, drifts of gravel rose and fell like the undulating dunes of a white desert. In less than nine months a terrible flood would sweep down this river. The raging Blanco would destroy hundreds of homes, fell an estimated fifteen thousand trees, and kill twelve people. As I hiked across the desiccated riverbed, however, the perils of flood were far from mind.

Water’s absence left the Blanco feeling empty and unsettled. It was all too quiet. Sun glare bounced off the pale river rock, and I squinted in the harsh light to read a shiny row of “No Trespassing” signs planted across one of the gravel bars. A small part of me wanted to pluck up the signs and toss them in a pile. That would make a statement. The public has a right to be here—a claim more than a few landowners dispute. Then I remembered a word of advice from an attorney who specializes in Texas river law, a murky world if there ever was one. “A book of statutes won’t stop a bullet,” he said.

Water’s absence left the Blanco feeling empty and unsettled. It was all too quiet. Sun glare bounced off the pale river rock, and I squinted in the harsh light to read a shiny row of “No Trespassing” signs planted across one of the gravel bars. A small part of me wanted to pluck up the signs and toss them in a pile. That would make a statement. The public has a right to be here—a claim more than a few landowners dispute. Then I remembered a word of advice from an attorney who specializes in Texas river law, a murky world if there ever was one. “A book of statutes won’t stop a bullet,” he said.

Gun-toting landowners patrolling the Blanco? You might think that’s a load of hyperbole. Maybe it is. When people talk about rivers, they tend to play up the dangers around every bend. Swimmers are sucked under low-water crossings. Kayakers crash into mazes of rock. But humans are the real hazard. The Blanco is subject to heated disagreements over sprawling development and rapacious “water grabs” that have depleted the river and threaten the plants and animals that rely on it. Paddlers, swimmers, and anglers must also navigate the conflicts between private property rights and public access laws. In Texas, where there is not enough water to go around, even small streams are worth fighting for. Especially the Blanco, which has been described as the “defining element of some of the Texas Hill Country’s most beautiful scenery.”

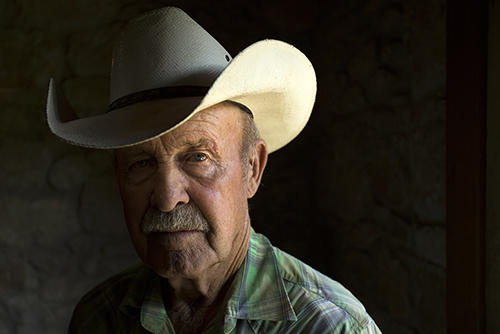

It’s true. The Blanco can be breathtakingly pretty, as long as you know where to look. The stream courses through sheer canyons, rolling hills, and flat, green valleys. On lazy afternoons, visitors enjoy cool flows and clear green swimming holes where bald cypress trees and craggy limestone bluffs offer much-needed shade from the summer sun. Before achieving national infamy for a flood that struck on the Memorial Day weekend of 2015, the Blanco was most widely known as an idyllic summer retreat and low-key tourism destination. But stories of confrontation are not uncommon. Fisherman Harry Hause tells one. He lives with his wife, Nancy, and their dogs beyond a tall river bluff near the Hill Country town of Wimberley. As he paddles downstream, Hause occasionally runs into fences erected across the riverbed. Twice, he and his fishing buddies were in the process of working their boats through a wire fence when they came face-to-face with the property owner. The elderly rancher was not happy to see them.

“I don’t know if he thought he was God or what,” recalls Hause. “If he was around, he would approach you. He made it perfectly clear he owned all this land. You’re talking to a guy armed with a shotgun, and you have to go through his fence. You don’t get too smart-assy. I heard from other people, he did that to them, too. People are very aggressive about their land rights. They don’t want you there; they think they own everything. They don’t care if you’re just boating through.” Gun-toting or otherwise, ranchers are a dwindling breed on the Blanco. The old-timers increasingly share the river with multimillionaires and billionaires who have turned riverfront ownership into an exclusive club that includes some of Texas’ most influential political donors; a part-owner of an NBA team; the founder of Mexico’s most powerful newspaper conglomerate; and George P. Mitchell, the late business magnate and real estate developer who pioneered hydraulic fracturing for natural gas, earning him the nickname the “Father of Fracking.” Throw in two of the Big Five trial lawyers who negotiated Texas’ legendary $17 billion legal settlement with the tobacco industry in the late 1990s, and you get the picture.

With so many riverfront ranches converted into vacation homes for well-to-do Texans, it might seem strange that an attorney, oil tycoon, or investment banker would harass a person for paddling or swimming the Blanco. But property rights are sacrosanct in Texas, ranking somewhere between love for God and Mama, and Hause’s story gave me pause as I contemplated the red-and-white “No Trespassing” signs on the gravel bar. The signs were mounted to metal T-posts, and I could have probably wiggled them free if I really tried. But I didn’t.

Abandoning any pretenses of civil disobedience, I scrambled up and down the dunes, through a world of white. Two years earlier, I had swum in water so deep here my toes could not touch bottom. Texas rivers are always changing, but the Blanco offers extreme evidence as it runs from bend to bend and day to day. On this morning, my toes were dry. Chalky river pebbles crunched underfoot, and outcrops of craggy limestone rose beyond the opposite bank. Here and there, small green clumps of switchgrass and Roosevelt weed clung to life in the gravel bars. They had taken root in the dry riverbed, where they were joined by a few leafy clusters of cocklebur. Even the plants’ colors seemed to fade in the August light. Sun-bleached rocks of many sizes were scattered like dusty bones across the riverbed.

There could be no doubt about it: this was el Ri?o Blanco, the White River. In this pale and barren place, I could almost picture the moment when a Spaniard stood on the banks of the Blanco for the first time in recorded history and gave the river a name.

The discovery of the Blanco, in 1709, occurred under fairly weird circumstances. You can read about it in a travel diary kept by Isidro Fe?lix de Espinosa, a prodigious writer and Franciscan friar who operated a mission on the far northeastern edge of Spain’s North American frontier. The mission was built next to a fortified military settlement, called a presidio, on the Rio Grande. Across the river lay the wilds of Texas. Although Spain had claimed the territory since 1519, the region was largely unexplored and ceded to native people.

Espinosa left his mission and headed north on April 5. He crossed the Rio Grande with the presidio’s captain, Pedro de Aguirre, fourteen soldiers, and a fellow priest named Olivares in search of members of the Caddo Indian tribe. Espinosa knew the Caddo as the Tejas people. His goal? Convince the Tejas to give up their ancestral homes and join him at his mission, where salvation and civilization were more conveniently gained. For his part, Aguirre just wanted to keep an eye out for any French people who might have been encroaching from settlements in Louisiana.

Riding on horseback, Espinosa was surprised and delighted by things he encountered beyond the Spanish frontier. He met Indians hunting mice, played with a baby buffalo, and named the San Antonio River. The searchers lost their way from time to time, but they pressed on, blazing a trail that would be followed by an increasing number of expeditions as Spain’s interest in Texas grew over the next decade. After about a week, Espinosa’s party reached a large Indian settlement near the Colorado River, not far from present-day Austin. The Indians were overjoyed to see them. They surrounded the Spaniards and “petted their faces” in a loving embrace. But these Indians were not the Caddo, so the searchers turned back. Espinosa wrote that he “shed copious tears on seeing such a multitude of souls without light and without knowledge of our Catholic religion.” Even so, he apparently did not invite these lightless yet unfortunately non-Caddoan souls to move in with him at his Rio Grande mission.

The Blanco makes its debut in Espinosa’s diary entry for April 16, 1709. On that morning, eleven days into the expedition, Espinosa crossed the San Marcos River two gunshot blasts from its headwaters in the present-day city of San Marcos. “Directing our course eastward through a forest of mesquite clumps and some elms we came, after a distance of about two leagues, to an arroyo with little water,” he wrote.

Two leagues is nearly seven miles. That’s the Blanco. From his descriptions of the region, Espinosa must have stumbled on the river in the vicinity of the dry section where I took my walk that sunburned morning. I like to picture Espinosa standing on the south bank of the Blanco, on a limestone bluff overlooking the whitewashed gravel and pale stone of the riverbed. He probably wore a long, loose tunic of dark twilled wool. His shaven head might have peeled with sunburn. Imagine fluffy clouds, blue skies, and the music of native songbirds. The splash of a Guadalupe bass—which swims only in Central Texas rivers like the Blanco—could have roiled the surface of a placid pool.

The river was lined with many oaks and some elms, Espinosa noted, “and is reached by leaving the crest of the hills in the direction of the northeast.” He must have seen the white rocks, too, and the ashen gravel, and the pale limestone bluffs. Espinosa viewed this river all of white, and he settled on a name: San Rafael Creek.